Induced Proximity: Are We Close?

By Dr Sheelagh Frame, sub-editor

A Perspective on the First Clinical Validation of PROTACs, and What Comes Next

PROTACs need little introduction and have been reviewed extensively (Zhong et al., 2024, Winter et al., 2024). The recent clinical validation of the induced-proximity hypothesis provides an important opportunity to step back and ask: how far have we come, and how far is left to go in realising the full potential of this new modality?

Origins: The First Demonstration of Targeted Protein Degradation

The original concept of PROTACs (PROteolysis-TArgeting Chimeras) was introduced in 2001 by Craig Crews and Ray Deshaies (Sakamoto et al., 2001). Their study described a chimeric molecule comprising a phosphopeptide ligand for the E3 ligase β-TrCP that was linked to a small-molecule ligand for the target protein methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2). This early construct was bulky and far from drug-like; cell-free extracts were employed for proof of principle to overcome limited permeability. Nevertheless, the experiment demonstrated something provocative: the ubiquitin–proteasome system could be redirected to remove (not merely inhibit) disease-driving proteins.

In an era dominated by classical occupancy-based inhibitors and frustration over the intractability of transcription factors and other “undruggable” targets lacking catalytic pockets, this demonstration was both disruptive and inspiring. The idea that protein removal might be more efficacious than protein inhibition, and the promise that the cancer proteome could be cracked open, catalysed two decades of discovery.

Those decades have delivered plenty: the shift from peptidic constructs to orally bioavailable (Kofink et al., 2022, Han et al., 2021, Rej et al., 2024) and even brain-penetrant degraders (Liu et al., 2022); a sophisticated understanding of ternary complex formation and its impact on the efficiency of ubiquitination (Sheik et al., 2024, Park et al., 2022, Ma et al., 2025); the critical role of linkers in determining degradation efficiency and cell permeability (Troup et al., 2020, Poongavanam et al., 2022, Dong et al., 2024) and, importantly, the first degraders entering the clinic (Ma & Zhou, 2025).

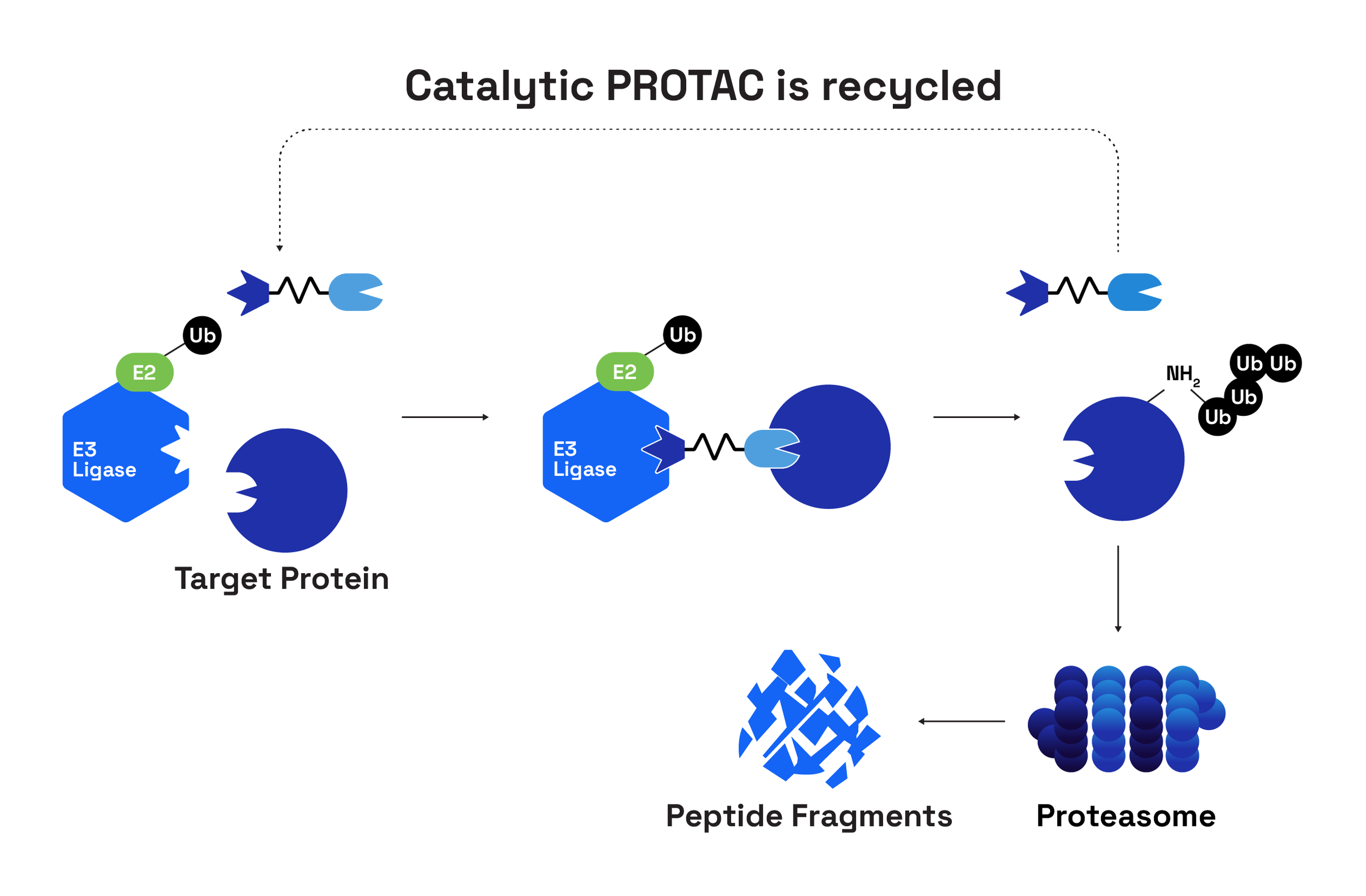

General overview of a PROTAC and their mode of action (Adapted from WuXi AppTec)

The Prequel to PROTACs: Induced Proximity as a Concept

Crews is widely recognised as the father of PROTACs, but the conceptual foundations lie deeper. Five years earlier, Stuart Schreiber and Gerald Crabtree introduced chemical inducers of dimerisation (CIDs) – cell-permeable molecules with two orthogonal binding surfaces that could bring proteins together to control signalling (Belshaw et al., 1996). Around the same time, Zhou and colleagues demonstrated that components of the ubiquitin machinery could be re-engineered to redirect degradation of endogenous proteins in yeast and mammalian cells by designing a chimeric F-box E3 ligase linked to a peptide recognising the retinoblastoma protein, pRb (Zhou et al., 2000). These earlier contributions established induced proximity as a programmable biological principle; subsequent PROTACs translated that from academic tool to drug-like molecule.

Twenty Years Later: Clinical Validation Arrives

2025 marked a landmark: the first clinical validation of induced proximity. The oral ER degrader vepdegestrant (ARV-471) demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) versus the ER antagonist/degrader fulvestrant in hormone receptor–positive breast cancer (Campone et al., 2025). The improvement was modest (5.0 months vs 2.1 months; p<0.01) and superiority was confined to a key ESR1-mutant subgroup (representing a large subset (43%) of the clinical trial population) which is, in some respects, a disappointing outcome for a field that has promised transformational gains. Still, (Ma and Zhou, 2025), this represents the completion of a journey from conceptual validation to clinical translation. Yet the limitations are equally instructive.

Reality Check: Undruggables, Catalytic Efficiency and Resistance

A key conceptual insight from the original papers was that PROTACs would benefit from a catalytic mechanism of action, with each PROTAC molecule triggering the destruction of multiple target molecules. Preclinical data supports this to a modest extent – doses can be reduced ~2-4 fold while achieving similar efficacy to inhibitors (Bondeson et al., 2015, Burslem et al., 2018, Khan et al., 2024). However, as a test of the theoretical advantages of ‘event-driven’ PROTACs over ‘occupancy-based’ inhibitors, fulvestrant is the wrong comparator. Fulvestrant is not simply an antagonist: it binds ER monomers, inhibits dimerisation, inactivates AF-1/AF-2, reduces nuclear translocation, and accelerates receptor degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Osborne et al., 2004). In other words, fulvestrant is itself a degrader, albeit mechanistically distinct. A cleaner comparison awaits the planned Phase 3 comparing pirtobrutinib (a non-covalent BTK inhibitor) with bexobrutideg (an orally bioavailable, brain-penetrant BTK degrader from Nurix Therapeutics) in relapsed/refractory CLL due to initiate early 2026 (Nurix press release). However, reduced dosing (frequency or absolute dose) will not be evaluated in this trial; both molecules are dosed orally daily (pirtobrutinib at 200mg and bexobrutideg at 600mg).

The clinical PROTAC landscape disproportionately favours proteins with pre-existing high-affinity ligands – kinases, hormone receptors, epigenetic readers – while classical undruggable targets such as MYC, STAT3 and intrinsically disordered proteins remain largely untouched. Ligandability remains the gatekeeper, prompting extensive dedication to novel ligand discovery by DNA-encoded libraries (DEL) and Direct to Biology (D2B) approaches (Osman et al., 2025, Rodriguez-Gimeno & Galdeano, 2025).

Resistance also emerges. This is an important point to reflect on, since one of the early theories was that targeted protein degradation may be less susceptible to the emergence of resistance since high affinity binding to the target protein is not a prerequisite for degradation. Progression of the tumours occurs quickly with vepdegestrant treatment, and early biomarker analysis implies that this is not due to inherently suboptimal dosing/degradation (the 500mg daily dose resulted in up to 89% ER degradation; Ma and Zhou, 2025). However, examples exist in vitro and in vivo of resistance via loss or mutation of the CRBN or VHL complex leading to reductions in ubiquitination and degradation, mechanisms distinct from those observed with classical inhibitors (Ottis et al., 2019, Zhang et al., 2019). Proposed solutions include E3 switching and even trivalent PROTACs recruiting more than one ligase (Imaide et al., 2021, Chen et al., 2024, Liu et al., 2024) - conceptually fascinating but operationally challenging.

Interestingly, several clinical findings suggest PROTACs may reveal their advantages in mutation-defined subgroups, such as populations representing an unmet clinical need due to their resistance to current standard-of-care. In addition to the vepdegestrant example, ARV-110 (bavdegalutamide) and its successor ARV-766 show strongest activity in AR-mutant prostate tumours (ESMO 2023 conference, Snyder et al., 2025), while bexobrutideg shows clinical activity in relapsed/refractory CLL regardless of resistance-associated mutations (OncLive).

Beyond PROTACs: The Next Generation of Induced Proximity Modalities

If PROTACs opened the door, the next decade will be defined by the widening corridor beyond them. Molecular glues, once thought serendipitous, are now being rationally designed, with Monte Rosa, Proxygen, Cedilla and Ambagon pioneering new strategies. DUBTACs offer targeted stabilisation of proteins by recruiting deubiquitinases and preventing ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Henning et al., 2022), opening up an entirely new set of targets not addressed by any current therapies outside of gene therapy. RIPTACs (Regulated Induced Proximity Targeting Chimeras) trigger proximity between a tumour-selective protein and a pan-essential protein, in principle, selectively disabling the essential protein only in tumour cells (Raina et al., 2024). Early clinical testing has begun (HLD-0915 clinical trial), though many questions remain with that approach, including the fate of the ternary complex, whether cell death is induced by mislocalisation, sequestration, or degradation of the complex and impact of RIPTAC binding to the essential protein in healthy cells.

So, Are We Close?

The first clinical proof of induced proximity is undeniably a milestone. But the deeper promise – drugging the undruggable, overcoming resistance, enabling tissue-specific therapeutics – remains ahead of us. What 2025 has demonstrated is not the fulfilment of the vision, but some validation of the concept. The next five years will determine whether induced proximity becomes a niche addition to oncology therapeutics, or a transformative pillar of drug discovery.